recollections with the JPL

recollections with the JPL

A gathering of recollections, regarding our collections.

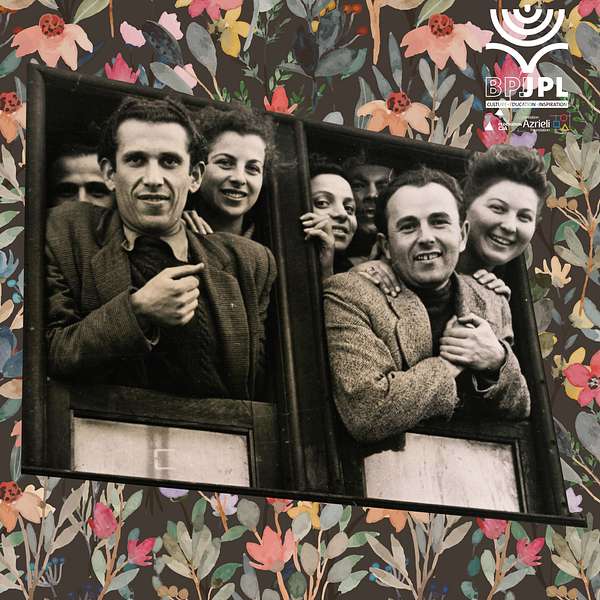

May 2024 marks the 110th anniversary of the Jewish Public Library. Our opening season of the recollections with the JPL podcast is a celebration of our Jewish leftist roots in Montreal. We weave together interviews with scholars, activists, teachers, and fellow archivists that discuss topics such as Jewish immigration to Canada, Jewish languages and culture, labour and feminist movements in the 20th century, and the diversity of political ideologies that existed within the 'left'.

recollections with the JPL

EP1: Upon Arrival

Use Left/Right to seek, Home/End to jump to start or end. Hold shift to jump forward or backward.

Episode 1: Upon Arrival

How well do you know the origins of Jews in Montreal? Episode One takes us through the great migration, the garment industry, and the humble beginnings of the Jewish Public Library.

Thank you to our featured guests, in order of appearance: Shannon Hodge, Pierre Anctil, Sam Bick, Moishe Dolman, and Eddie Paul.

recollections with the JPL is a production of the Jewish Public Library Archives and Special Collections.

Thank you to all of our guests: Pierre Anctil, Sam Bick, Moishe Dolman, Shannon Hodge, Aaron Krishtalka, Melanie Leavitt, Eddie Paul, and Ester Reiter.

Visit JPL Curates to see licensing info, guest bios, related materials from the JPL Archives and Special Collections, and our further reading guide featuring works from JPL's catalogue.

Info:

Donate to the Jewish Public Library

Follow @jplarchives and @jpl_montreal on Instagram

Production and editing by Ezell Carter and Ellen Belshaw

Research support by Leah Graham, Sam Pappas, Maya Pasternak, and Eddie Paul

Mastering by Josh Boguski

Theme song and music by Danijel Zambo

Sound effects provided by Pixabay and the JPL Archives

Thank you to our sponsors, the Azrieli Foundation and Federation CJA

[00:00:00] Shannon Hodge: And if we look at the Jewish left, so it wasn't just a labor movement, it was poetry, it was theater, it was music, it was schools, um, just like, you know, this pantheon of just absolutely stunning movement.

[00:00:26] Ellen Belshaw: I'm Ellen Belshaw.

[00:00:27] Ezell Carter: And I'm Ezell Carter.

[00:00:29] Ellen Belshaw: And you're listening to Recollections. We are coming to you from the stacks of the Jewish Public Library Archives and Special Collections. Thank you so much for joining us.

[00:00:38] Ezell Carter: May 2024 marks the 110th birthday of the Jewish Public Library. We are celebrating with the launch of this new podcast in which we reflect on JPL and Montreal's rich leftist history.

[00:00:53] Ellen Belshaw: In this series, you'll be treated to a sampling of Jewish leftist history interviews with scholars, activists, and scholars alike. Teachers [00:01:00] and fellow archivists.

[00:01:01] Ezell Carter: A gathering of recollections regarding our collections.

[00:01:06] Ellen Belshaw: Welcome to recollections.

[00:01:19] Ezell Carter: Okay. All right, Ellen, let's do it. Let's talk about it.

Yeah.

Why this podcast? Why this topic? Why now?

[00:01:28] Ellen Belshaw: The easiest first answer is the 110th anniversary of the library. Of course. So, we've been looking back on our history, the history of the library, and uh, finding a lot of leftist threads that we didn't necessarily know were there.

I mean, we've only been at the JPL for two years, so we're very new to this topic.

[00:01:47] Ezell Carter: It's true. And I have only been in Montreal for four years, so I'm even newer, I guess.

[00:01:52] Ellen Belshaw: I've got almost a decade on you, but that's, I'm still learning. Many things every day. [00:02:00]

[00:02:00] Ezell Carter: I think for me, uh, it's about Understanding how much I have benefited from the work of the left.

Totally. And even the left, right, is a contentious Phrase. Oh, yeah, we're gonna get into that. Oh, yeah. Yeah, most definitely. I mean, there's

no way not to.

[00:02:16] Ellen Belshaw: Oh, yeah, the labor organizing is a very strong part of this history.

[00:02:21] Ezell Carter: Yeah. And as a woman, I cannot possibly ignore the fact that so much of the rights that I have right now are due to the people that came before me.

Um, I think for me and, and maybe for you, I had no idea how much of that was tied into Jewish immigration.

[00:02:38] Ellen Belshaw: I had a little bit of an idea, but working here has definitely opened my eyes to how integral Jewish history is to Montreal history, for sure.

[00:02:47] Ezell Carter: So, yeah, I think that that's a good answer for all of that.

I think, as far as why a podcast, why a project taking this form. So, Ellen and I are not subject [00:03:00] matter experts. We do consider ourselves a little bit of history buffs, but, um, we are coming out of a space that is a communal endeavor, started that way, continues to be that. So we had a lot of people willing to help, um, who had this as their lived experience.

[00:03:21] Ellen Belshaw: Or as their whole professional career. We have a bit of a range of people that we've spoken to on this who, um, come from this academically, uh, from their own history. So there's a mix of voices you'll hear.

[00:03:34] Ezell Carter: Yeah. I, yeah, absolutely. We wanted to get a diverse mix of voices. I mean, because especially too, is you'll hear.

Again, in a future episode, the left was a diverse mix of voices. There was no one right answer, no pun intended. Um, and so I think that we

were really fortunate that when we started, you know, the whispers started going around about the [00:04:00] project, people wanted to help. Um, and also we live in this age now where, uh, we can rely on technology to craft.

a new form of storytelling. Um, and that's kind of what we're trying to do here.

[00:04:18] Ellen Belshaw: So it's a really broad topic. We can only really scratch the surface. On that note, are you ready to get started Ysel? I absolutely am. Yes. Okay. Uh, we start this episode along the main in the early 20th century with Pierre Antille, author and educator focused on the history of immigration in Quebec and in Canada and of Jewish culture in Montreal.

[00:04:38] Pierre Anctil: Well, the main Boulevard Saint Laurent, it was first La Rue Saint Laurent. in up to 1905, um, was the main thoroughfare in Montreal from the river all the way up to Laval. So everyone, anyone moving around in [00:05:00] Montreal had to go and be on that artery. And the Jewish community arrived either by rail or by boat.

by boat in the port and moved up into Montreal along the Saint Laurent axis, I mean. Um, so for, uh, I'd say a period of just before World War I to until just after World War II, this is where, for 30 years or something, this is where most of the Jewish institution of Montreal were. Around Parc Jeanne Mance also, just next, which is Fletcher's Field, and Mordecai Richler's novels.

And, um, there was a dense city. There was, uh, people live right next to the garment factories where they worked. They could go to a synagogue on foot. They could get all they needed in the [00:06:00] immediate surrounding environment. And so it was a, it was a place, it's a place where the Jewish community formed and thrived for at least 30 years.

The main was not only Jews, but almost every form and shape or type of immigrant that was coming into Montreal at the time. The Italians established themselves just north of the Jewish community. Uh, the Ukrainians and the Slavs and others. So, it was not just a Jewish enclave, but it was an immigrant enclave, where Yiddish and the Jewish culture was dominant.

For French Canadians it was something else, because French Canadians were not immigrants. Or if they were immigrants, they were immigrants from the outlying areas, they came from farms, but they're still the same country, they spoke the same language. [00:07:00] It was used by French Canadians as a place. of trade.

They could obtain merchandise, often from Jewish stores, or as a place of entertainment, because of the clubs, the striptease places. You could also, uh, do, uh, illegal betting. I mean, it was a place where French Canadians congregated for other reasons. But it was also very central to French Canada.

Prostitution as well. Um, all kinds of cinemas, theaters, including Yiddish theaters, to which I suppose French Canadians would not go so often. And, uh, as a teeming place, it was a place full of energy, on, on about five streets on each side of Boulevard Saint Laurent. So, it was, it was, uh, It's the place where immigration arrived and where immigrants Canadianized.

In all of Canadian history, it's a central place. For French [00:08:00] Canadians, it's a place where you went to, to reach to the outside world, in other words.

[00:08:09] Sam Bick: The two ideas that I think are helpful are the dissolution of Poland and Lithuania in the late 1700s and the Pale of Settlement.

[00:08:23] Ezell Carter: Sam Bick is a PhD student in York University's history department and the former host of Montreal based anarchist Jewish podcast Traith.

[00:08:35] Sam Bick: And both of those I think are helpful geographic historical events that can help understand how we get left Jews in Montreal in the early 1900s.

In the late 1700s there are several empires. In that part of the world, Prussia, Austro Hungary, uh, Lithuania and Poland, or Poland and Lithuania, and the Russian Empire. And there's a bunch of conflicts in the late [00:09:00] 1700s, and the area that had what, the most amount of Eastern European Jews that we understand today, It, a lot of which was in Congress, Poland, uh, Belarus, Lithuania, Latvia, parts of Poland, as I mentioned, Ukraine, they all fall under the, the Russian empire, Jewish incorporation into the Russian empire is happening at a time when the Russian empire is changing tremendously capitalism, what people call modernity, imperialism ideas of liberalism are.

Spanning the globe, there's a lot of change happening in Russia, Jews who were previously under a different relationship, many of whom relationships, for example, with the Polish kingdom, uh, are now facing kind of a new series of dynamics. And Russia's initial response to this is to kind of outline a section in the West where most of the Jews were already living.

called the Pale of Settlement. And that is kind of the geographic area that Jews more or less have [00:10:00] to stay in. By the 1860s, 1870s, 1880s, Russia's undergoing a change from a, like a top down agrarian society, peasants feudalism, to an attempt to kind of mirror or, or have their own version of like Western industrialization, like Germany or England.

And so, uh, A lot of, uh, industrialization, a lot of factories, people leaving the countrysides, moving to the urban centers. And it's kind of in this context that all these new ideas are coming together. Uh, particularly in Russia, people are not happy with the current, uh, social, political, economic, political situation.

set up that puts a ruling, uh, monarchy at the top. And so there are people, people have different articulations of, of how to change society. And it's within this context that that Jewish and non Jewish subjects of the Russian empire are, um, uh, subscribing to creating, building, and thinking about different ways of living.[00:11:00]

[00:11:21] Eddie Paul: In 1901, almost 7, 000 Jews had settled in Montreal.

[00:11:28] Ellen Belshaw: Eddie Paul has worked within Library and Learning Services at the JPL for over 30 years and is the innovator behind the Special Collections Outreach Initiative.

[00:11:38] Eddie Paul: Twenty years later, this number had grown to over 45, 000.

[00:11:43] Sam Bick: Eastern European Jews start immigrating to Montreal in the early 1900s.

The big wave is between 1909 and 1913, right before the First World War. And that's more or less where Eastern European Jewish immigration [00:12:00] ends until the Second World War. But, so to get a context, you have a lot of immigrants coming in. Eastern European Jews who are leaving, uh, political turmoil upheaval, the 1905 revolution in, in the Russian empire created a lot of change and a good deal of antisemitism as well.

So you have a lot of Eastern European Jewish migrants coming to North America.

[00:12:22] Pierre Anctil: It's interesting to note that the, what we call the great migration, meaning the massive arrival of East European Jews from the Russian empire. took place or began almost simultaneously as the 1905 insurrection in Russia. So when young Jews began arriving here, they were fired by the revolution, by leftist ideas.

Uh, they were, uh, they had all the trappings of left leaning militants and activists. So. This [00:13:00] community was far more to the left than any other.

[00:13:03] Sam Bick: There's been a lot of academic and intellectual debate about whether people brought radicalism with them or became radicalized here, but not just for Jews, for all groups of European people.

immigrants? I think the answer often is it's both. And so it's not like these foreign, all these foreign ideas, like it's, it's, it's a question of both. It's, it's, it's a, it's a hybrid answer that both, um, people brought radical ideas with them, but when they came here, they were faced with new realities that altered and changed, uh, ideas that they brought with them.

And then they sent those ideas back and they created new ideas.

[00:13:37] Pierre Anctil: In Montreal and in Canada, especially comparing to French Canada and English Canada, which were much more conservative and traditional societies. And, and if you compare with immigrants from other origins as well in Europe. By the first decade of the 20th century, this community, The very complex [00:14:00] and broad Jewish community of Montreal.

I would say that, that socialism and, and the left leaning ideologies were becoming the dominant political trend and it, it permeated everything. in institutional development and the way people behave, how they related to work, and how they conceived of the world for themselves and for the future. The other element is that the level of education was much lower in all communities, especially among French Canadians.

Um, it changes something when, when a large percentage of the population doesn't read well and cannot read a newspaper. And do not have access to an, the enlightenment that the education years brings to the individuals. do not have, uh, [00:15:00] credentials. Um, and so the, the, um, milieu was often here, was often the victim of demagogues, people who, who would, you know, say anything just to get elected and the people didn't have enough education.

Not that they were stupid, but they didn't have that possibility of improving their lot by education. The exploitation of workers was much harsher as well. People worked 60 hours a week at the beginning of the period. Wages were much lower. People had a much lower standard of living. Health conditions were incomparably bad.

The mortality rate of children was much more than today.[00:16:00]

[00:16:04] Moishe Dolman: Living conditions were terrible. I think that was when you, the issue of like working in the garment industry. You have a particular thing here, even in the old country, Jews tended to work in the garment industry. There's a historical reason for it. And that is, you know, in the old religious society, there's something called Sha'atnez, which is the forbidden mixture of wool and Lenin.

Oh, linen, that was a Freudian slip? Wow, that's good.

[00:16:33] Ezell Carter: Moishe Dolman is a Yiddish teacher, translator, and activist in left wing and anti authoritarian causes, and he's long considered the Jewish Public Library sacred grounds.

[00:16:47] Moishe Dolman: And so Jews already are starting to make their own clothes. When North America is industrializing and urbanizing, which is in Canada, it's one generation [00:17:00] later than in the United States.

There's a tremendous demand for in the new cities for ready to wear clothing. And so what you start is you have a situation where not all Jewish immigrants are working in the clothing industry, but the clothing industry is dominated by Jews, both in terms of the employers and the workforce. And, um, Most, most Jews are working somehow or other in the, or tied to the ready to wear clothing industry.

The problem when it comes to the situation of the Jews is that it's the sub, the sweatshop system, which is that the, Industry is organized in such a way that it's not just one company that produces everything from top to bottom, but you have a wholesaler that subcontracts out work. And so they're competing with all the other subcontractors for the lowest possible to [00:18:00] make the lowest bid.

And that subcontractor subcontracts out various pieces of the labor of the labor process. And so of course, then they're competing with other people to bring things down to the lowest common denominator in terms of costs. Mostly wages and then the workers themselves often. They're not working in factories.

You're working for a subcontractor Or a sub sub sub subcontractor and they're you're working in your own house. You're working with People who, your, your whole family is employed working for practically nothing in very unsanitary, crowded conditions, long hours, um, extreme, 70 hours a week for practically nothing.

And, um, to make other people rich, basically, at the top. Often the difference between a boss and a worker was very little. A sub sub subcontractor was also probably working at home over a sewing machine, but was bossing somebody else around. [00:19:00] This is what led to the eventual growth of the Jewish trade, first of all, of the Jewish trade unions, of the Jewish revolutionary movements, general left wing movements.

[00:19:13] Eddie Paul: Yeah, in Toronto, um, I think there was something like 70 to 80, um, garment concerns along Spadina Avenue within a few, within a small block radius. And yes, the working conditions were horrible. And that is where the trade union movement started. It started with dressmaker, dressmakers union strikes, uh, Winnipeg as well.

Um, there was really no difference between the three cities in terms of the conditions that. I think the only difference in Montreal, this was certainly the older community. It was the oldest of the three communities. But, um, yeah, people were impoverished. Um, and, um, but because of the latent anti [00:20:00] Semitism, um, that prevailed in sort of Canadian society, it was the only, it was really the only industry that Jews could work.

And I have, I mean, I can tell you a personal anecdote. My father tried to get into engineering school, um, at Universidad de Montreal, and he was told in no uncertain terms that, you know, they weren't accepting Jews that particular day. This was fairly common. He tried to get jobs in the aeronautics industry, same, you know, same issue.

So Jews basically just got jobs wherever they could because they had families to support. Um, this was really the case in Winnipeg, and Toronto, and, of course, Montreal. Now, um, Jews were seldom hired as sales clerks or bank clerks. Um, there were a lot of industries and places of commerce that were just closed off to Jews.

Um, and obviously professional positions in engineering or law firms were [00:21:00] completely out of the question. So they took whatever jobs were available to them. Um, and the booming garment industry here, which employed more people than any other, they were always on the lookout for laborers. Now, many Jews had tailoring experience from back home, and those who didn't learned the skills very quickly.

Between 1870 and 1930, uh, the needle trade employed more workers than any other industry in Montreal. 40 percent of them were Jewish. The rest of them were mostly French Canadian. And this grew to about 75 to 80% of all of Montreal's Jews who worked in the garment industry in some capacity. And this was born out, because the people in my father's generation were all in the in the shmata business.

Um, everybody, all of, all of his friends, many of his relatives, uh, people that I grew up with were all in the shmata business. And initially, you know, ultimately what happened was, uh, all of that [00:22:00] business, when it got outsourced to the Orient. And, um, there was no manufacturing left here. You know.

[00:22:17] Moishe Dolman: This is a reality that younger generations of Jews perhaps don't realize it. But when I grew up, all the kids around me were Jewish kids. Their parents worked in factories. My mother was a homemaker. My parents, their parents worked in factories or they were taxi drivers when it seemed every taxi driver in Montreal.

Was Jewish or they had small businesses a little grocery or a newsstand on the corner or Downtown all the newsstands used to be Jewish or petty tradesmen petty, um, you know, shopkeepers and what have you. I knew there was such a thing growing up as Jews who were professionals or Jews who were very wealthy.

[00:23:00] There were those, but we knew none of them. I knew none of them myself. Only the wealthiest Jews lived among Sherbrooke to the point where, if people remember, the eccentricists uh, theater on St. Lawrence Quarter Milton. That was originally a synagogue. And when they built it there on St. Lawrence and Milton, people said, how can you have a synagogue all the way up the hill?

Who's going to walk all the way from St. Lawrence to St. Lawrence? from, you know, the Jewish area to go to a synagogue on Milton within a few years. That was too far south, not north. Um, for many, many years, Jewish culture was situated primarily in the Monument National, was where all the Jewish theater took place.

That was corner What we now call Rene Levesque in St. Lawrence that Jews used to rent it from the St. Jean Baptiste Society, the owners. Um, that was where the focus of Jewish life [00:24:00] originally was. Um, it progressed, I don't mean progressed in a good sense necessarily, but it moved continuously further and further north.

[00:24:13] Eddie Paul: The terms Uptown and Downtown Jews were really just shorthand. for a kind of sociocultural divide. Um, in the thirties and forties, Montreal was kind of bisected by a rough line of demarcation, um, that, uh, divided the densely populated urban areas around the plateau on either side of St. Lawrence Boulevard or the main.

Um, and this is where most of the new Jewish immigrants had settled. They started off from the area in old Montreal and they moved north. Um, and the so called downtown Jews were the ones who populated those streets on either side of St. Lawrence Street, St. Urbans Street, north to Mount Royal. [00:25:00] These were the streets that were popularized in Mordechai Richler's novels, The Apprenticeship of Dodie And the uptown Jews who had been here for a little bit longer.

lived in the more affluent areas of Westmount and NDG and the western parts of downtown, kind of the Golden Mile, um, area. Um, and so the terms uptown and downtown Jews, uh, were, you know, they're not, they're not generally used in, in, you know, serious scholarship, but when you hear those terms used, you're really referring to new immigrants and people who had already, you know, been established here.

It's the same situation in Amsterdam in the 17th century where you had a Svartic population who had been, who had settled in Amsterdam for centuries, and the poor Ashkenazic population who were escaping pogroms in, in Poland, were, they would have been the equivalent of the downtown Jews in Amsterdam.[00:26:00]

Same idea.

[00:26:02] Pierre Anctil: It is a much spoken, much discussed notion of the uptown and downtown in Jewish Montreal history, and that the uptown who were just one generation ahead. from Eastern Europe often, but had, had a chance to improve their situation, looked down upon the new arrivers and felt that they were shameful, that they, um, that they made the Jewish population of Montreal look bad.

Um, and Mortimer B. Davis, The, uh, wealthy owner of the, uh, Imperial Tobacco Company made important efforts to finance institutions and publications which promoted assimilation, which is one of the reasons why Jews accepted [00:27:00] the 1903 law, which made Jews Protestants for the purpose of education.

[00:27:17] Eddie Paul: In the early 1900s, um, Jews didn't have the same constitutional rights as Protestants and Catholics. And this, uh, culminated in, um, in an event that happened, uh, in 1903 when a little boy by the name of Jacob Pinsler, uh, won a scholarship to, um, uh, attend a high school, but, uh, he was declined because the Protestant school board, and the Protestant school board at the time had administered all of the Protestant schools where many Jews, um, were, had attended, they, they argued that the Pinslers didn't financially contribute to [00:28:00] the school because They, they rented their, their flat.

They were not property owners, and since property owners pay taxes, they were not really supporting the, the school system. So the Pinsker sued with the support of the Jewish community. Initially, the Quebec Superior Court upheld the board's position because only As I said, Protestants and Roman Catholics had constitutional rights.

Um, now this led to, uh, some fallout, as, as it does. And in 1903, the provincial government adopted the Education Act, which stipulated that Jews would be considered Protestants. for educational purposes, and the Protestant board would receive funding based on Jewish enrollment. Uh, this was obviously a contentious issue.

It remains one of the sort of milestone events of Jewish history in Quebec. [00:29:00] Another milestone event in the history of, um, Jews in, in Quebec. Um, there was obviously growing antisemitism in the 1920s. Um, um, And there was tension between the Jewish community and the Protestant school board, the Protestant school commission.

And, um, as is often the case, there was a response from the Catholic church. Um, and because Jews had been designated honorary Protestants, as, as though that was even a thing, um, the Quebec premier at the time, Um, referred the Education Act to the Quebec Court of Appeal. Initially, the court ruled that the Law violated the BNA Act, the British North America Act, and it was appealed again to the Judicial Committee of the Privy [00:30:00] Council in London, so a lot of lawyers were getting wealthy, which is also, you know, very often the case.

And finally, what happened in 1928 was that, um, Section 93 of the Act, uh, was stipulated that, um, Catholics and Protestants had guaranteed educational rights. But the Jews had no legal rights in the Quebec public school system. And it remained in force until the Quebec government scrapped the confessional school system and replaced it with linguistic school boards.

And this happened in the 90s. So when I was going to school, I was going to a PSBGM school, a Protestant school board, even though 90 percent of the students in my, in my elementary and high school were Jewish.

Just across, um, Carré Saint Louis on rue Saint Denis, there's a building called l'Institut de Tourisme et d'Hôtellerie du Québec. And amongst other things, [00:31:00] it's a, it's a professional training institute for, um, students studying tourism and hotel and restaurant management. But back in 1913, it was the Aberdeen School.

It was an elementary school. And in February of that year, Miss McKinley, who was a grade six teacher, called her Jewish pupils dirty and declared that they should be banned from the school. And that outburst triggered, um, a political storm at the school where Jews had constituted majority of the Uh, news spread quickly, um, from the grade six classroom to the other senior students, and hundreds of Jewish pupils went on strike.

They congregated in the park, Keres and Louie, and they organized pickets. Um, some of the strikers marched to the Baron de Hirsch Institute and the newspaper office of the Kennedger Adler to demand that action be taken against Jews. Miss McKinley. Now, eventually Miss McKinley apologized, [00:32:00] but, um, prominent Jewish community leaders who had negotiated with the principal and with the PSBGM, um, the apology, even though she had expressed her regret for having made inappropriate remarks, um, it was really not perceived as an apology.

And what it did is it really bold faced, um, kind of nascent anti Semitism. within the sort of Anglo Jewish culture of, of Montreal. Dedication Ceremony Jewish Public Library

[00:32:35] Pierre Anctil: Anti Semitism was imported from Europe. It, it, something that emerged in Germany late in the 19th century, uh, was redefined by the French in Affaires de Refus or in publications. It existed in Great Britain. So it [00:33:00] reached Canada from those. Regions of Europe, which were the closest to Canada, economically and politically.

So Germany, France and Great Britain contributed a great deal. In ideology, in ideas, in notions, and people absorb these events and these notions here, began to look at Jews as the French or the English or the German would. Um, one has to distinguish between a French language version and an English language version in Montreal.

There's at least two versions. Anglo Protestant Canadians defined their own form of anti Semitism, which was not like the Franco Catholic form. Um, what defined French Canadians is they took [00:34:00] their notions from the teachings of the Catholic Church. Before the Vatican Council of the 60s, the Catholic Church was the main vehicle for hostility to Jews.

French Canadians went to mass. They absorbed antisemitism in the liturgy, in the teachings, in the preaching. And often we find, um, that when Jews would say, well, this, sorry, this is antisemitic. And the French Canadians would answer, no, it's not. We're not anti Semites, we just repeat what the priests say. We just repeat what our masters or our forebears say.

If the church says it, it can't be wrong. See, that was the problem. The objections of the church were doctrinal. In other words, a Jewish person is someone that rejected Christ and [00:35:00] is not likely to be a good citizen, a good person, to be welcomed in the Catholic environment. The British said something else.

They said, for racial reasons, we should reject. This is more the German version. For racial reasons, we should reject Jews because they contaminate our people. French Canadians didn't say this because the notion of the Church is that all humanity. can be converted to Catholicism. And these racial barriers are more superficial.

It was perceived at the time that the quicker East European Jews would learn English and behave like good Protestants, the better it would be for them and for the Jewish community altogether. Uh, well, it doesn't work that way, of course. It takes more time. But, uh, we, we see that indeed, um, that was one of the solutions proposed.

The other solution [00:36:00] was a solution proposed by the Jewish Public Library and other institutions that yes, you have to integrate, assimilate, become good citizens, but remain Jews. And to remain Jews, you need Jewish institutions, such as the Jewish Public Library.

[00:36:21] Dedication Ceremony for JPL, October 1953: I remember a hot summer afternoon in 1912 when my late father, Ruben Breinen, turned the key in the door of a modest house on St. Urban Street.

The first home of the Jewish Public Library was there, and a small group of friends helped them to found it. I remember that when my father spoke from the steps of that humble house, he said, [00:37:00] he was firmly convinced that this small library, would grow into one of the proudest achievements of our community.

[00:37:09] Pierre Anctil: There were many divisions in the Jewish left here. Um, one division was, left Zionism or, or left nationalists on the one hand, and then on the other hand, the internationalists. So those in favor of a Jewish state or the support for a Jewish people, and those who wanted to be part of the general overall revolution, which would engulf all of western society, basically the communists.

So these differences were major and kept these people apart. They were all left leaning, but they did not see the world the same way. Um, this was visible in many other [00:38:00] ways. Um, the, the, uh, unions that became organized, the, uh, circles, uh, intellectual, literary, artistic, uh, bore the, uh, differences. Some of them were more internationalist and some were left leaning.

Uh, the Jewish public library, of course, was not internationalist in that sense. It was leaning towards a form of diaspora nationalism.

[00:38:31] Sam Bick: The literal books that became the Jewish Public Library, or the literal books that eventually would serve as the first books in the library, were the books that came from the lending libraries of radicals, Jewish radicals in Montreal, and also that Jewish radicals in Montreal were the ones who Who are deeply involved in creating the Jewish public library, both the first attempt in 1912, and then again in 1914.

So within the context of Jewish political movements in Eastern [00:39:00] Europe there, and this is not, um, unique to the Jewish experience. It's very much common across the European leftists of the time. There's a big investment or understanding in the idea that culture and revolutionary politics go together. The idea of people building themselves up, having reading circles, learning.

There's a huge emphasis on culture as part of the struggle for the working class. And so in Montreal, uh, the first attempts to create the public library. You know what, I think Moïse should tell part of this story, but the Jewish People's Library, let's say, because that was the name of the institution for the first, uh, 20 years of its existence.

[00:39:41] Moishe Dolman: People's Library and People's University.

[00:39:45] Sam Bick: Exactly. I've heard this story from you several times in my life.

[00:39:52] Moishe Dolman: And you'll hear it several more for sure.

[00:39:54] Sam Bick: Please. I look forward to it. Yeah, so this people's library, um, in 1912 [00:40:00] is when there were attempts, they had a bunch of public events in the spring leading up to a big strike, the first big, or one of the major strikes that happened in 1912. Um, and the public library was started by figures like Brynan, Khazanovich, Moses Shmulson, different characters who were involved in the founding several years later.

But yes, in, in 1912, as a strike is going on, there are attempts to organize what becomes the library. And they have hour, they have library hours that are set up to accommodate workers who are working during the day. For example, it is very much, it's called the People's Library and People's University.

There's a real self development pulling yourself by your bootstraps education concept going on. Uh, and, uh, this is really like seen as a site for Uplifting the workers and, and the Jews kind of at the same time.

[00:40:56] Moishe Dolman: And it opens on May Day, incidentally. [00:41:00]

[00:41:00] Pierre Anctil: When you read the first annual report, which was published in 1915, it's amazing the extent to which people invested time and energy voluntarily to support the Jewish Public Library, to become a member, to donate books, to raise funds.

It's amazing. It's, uh, it's a beehive of activity. Uh, without. government funds and with basically no support from the wealthier segment of the community who did not really entertain much hope or interest in the Yiddish culture. And, um, the, the ideas which was, were imported from Eastern Europe found a place in the Jewish public library to, to be voiced out, to be discussed.

You know, we, we forget. 1914, we [00:42:00] say, well, that's the beginning. But, but the beginning of the community altogether is, is basically that day two. When you look at the chart of Jewish immigration to Montreal or Canada, it begins in 1904. There's almost no immigration before. And so, people are still getting off the boats.

Yes. When the Jewish Public Library was founded, and it was founded because the There was a surge in numbers. Suddenly, in 1911, there were 30, 000 Jews in Montreal. Enough for a newspaper to appear, for schools to be founded, and for a cultural center to exist. There was a Jewish public for it now. And that's this moment.

A unique moment which, which saw the appearance of the Jewish public library. Uh, Yiddish Folks Bibliothek. It's interesting. A folks bibliothek, of course, has a different meaning. It means the place [00:43:00] where the Jewish people is found and its library exists. Uh, I was stunned at the extent of the involvement and how much people invested in the institution, how much desired its existence.

And, um, It's interesting to consider that, uh, when it opened, it had only 1, 500 books. Most of which came from the Polytion Library, which existed a couple of years before. And, um, a 3, 000 budget. It's, it's amazing. All of this, given by the people. You know, in a nutshell, the Jewish Public Library is the Jewish community in its history and its destiny, starting in 1914.

Um, It played a key role in the first half of the 20th century in, in regrouping [00:44:00] all the cultural forces, bringing writers, thinkers, Yiddishists, activists, political militants, all together in one place to share what they had as a Jewish culture, Yiddish culture, with, with sometimes a great deal of differences in perspective, politically and otherwise, but that's fine.

It was perceived as a place where people could merge, come together, not as a place where People would be forced to adopt a position which was common to, to all. It did a lot to educate Jews as to their own culture, but also as to what they could expect from this country. To become better citizens, to master the English or [00:45:00] French languages, to obtain, uh, Competence in certain domains and find work.

Um, I think it was basically at the beginning, a school for adults, um, where people improve their notions, um, become, became better read, more cultivated and exposed to all forms of, um, work. cultural manifestations. Uh, it did a lot to organize collective forces.

[00:45:50] Ezell Carter: Thank you for joining us today as we started our deep dive into Jewish leftist history in Montreal. Tune in for episode two as we learn more [00:46:00] about the radical roots of the Jewish left, including the role of reading circles, the richness of Yiddish culture, and an introduction to the key players of the movement.

[00:46:11] Ellen Belshaw: A huge thank you to our guests. Pierre, Sam, Eddie, and Moishe. Their in depth biographies can be found in our show notes. recollections is the production of Jewish Public Library Archives and Special Collections. Additional production, editing, and operations by Ellen Belshaw and Ezell Carter. Research support from Leah Graham, Sam Pappas, and Eddie Paul.

Sound design by Josh Boguski and Ezell Carter.

[00:46:37] Ezell Carter: Musical score by Danjiel Zambo. Sound effects provided by Pixabay. Thank you to our sponsors, the Azrieli Foundation and Federation CJA.

[00:46:47] Ellen Belshaw: You can find out more about this podcast and all of our other happenings at jpl curates. org or sign up for our Archives and Special Collections newsletter, Der Zamler.

You've been listening to recollections. [00:47:00] This is Ellen Belshaw

[00:47:01] Ezell Carter: and Ezell Carter signing off in solidarity.

[00:47:16] HOSTS: Do you say it first or do I? Me? And you say it and you're listening to Recollections? Okay. But give it the theater kid.

Theater kid. Yeah. Okay.